Ks. Christopher Robson

Countertenor

BBC RADIO 4 INTERVIEW

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08rq6dn

REVIEWS/CRITICS

It is not only the choral singing that puts this new Messiah up with the very best. The soloists too each bring something unique and individual to their roles. Christopher Robson has recently been electrifying audiences with his performances, and when he opens his mouth on this recording he may as well be plugging us all into the (electricity) mains. For his performance of “But who may abide” alone I would go out and buy this Messiah even if the rest were trash.

CD Review Magazine (Handel’s “Messiah”, Chandos Records CD)

Christopher Robson is the remaining member of the solo line-up. His clear voice, sure intonation and ability to achieve light and shade make for rewarding listening.

Gramophone Magazine (Handel’s “Messiah”, Chandos Records CD)

The

Meridian CD is coupled with Vivaldi's beautiful setting of Psalm 127,

Nisi Dominus, a piece hardly less substantial than the Laudate

Pueri,

though probably more familiar to discophiles and concertgoers. The

soloist is the alto Christopher Robson, who gives a sensitive,

authoritative and polished performance which I very much enjoyed

Gramaphone Magazine (Antonio Vivaldi "Nisi Dominus", Meridian Records)

The cast in this version are to be commended not only for the quality of their singing but for the precision with which they pronounce the words, making it a delight to listen. Christopher Robson, the countertenor, is a memorable Artaxerxes.

Contemporary Review (Thomas Arne's "Artaxerxes", Hyperion Records CD)

... but in the end I decided, patriotically, to choose first the recording of Arne's Artaxerxes under Roy Goodman, an entertaining work in which Catherine Bott and Christopher Robson sing with particular distinction.

Gramophone Magazine Awards (nomination for Thomas Arne's "Artaxerxes", Hyperion Records CD)

With a rare concentration and feeling, the aching beauty of Christopher Robson's counter-tenor could instil 'Hope' into any breast.

The Independent (Monteverdi's "L'Orfeo", Decca L'Oiseau Lyre CD)

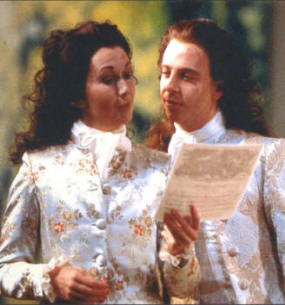

GLYNDEBOURNE TOURING COMPANY's staging of Handel's

Theodora was a great improvement on the performance at the summer

festival. Peter Sellars revised and rehearsed his production, which now

made a stronger dramatic impact than before. Anne Dawson sang Theodora

with melting beauty of tone, while conveying all the Christian martyr's

fortitude. Susan Bickley was most supportive as Irene. Countertenor

Christopher Robson as Didymus and his brother, tenor Nigel Robson, as

Septimius were quite outstanding as two of the Romans charged with

carrying out the death penalty on those who denied the Roman gods. Harry

Bicket conducted.

Christopher Robson, one of the few countertenors to possess the combination of staying power, strength of voice and genuine acting abilities, all vital in the opera house, sings the role of the Refugee quite beautifully, summoning a whole range of emotions and conveying a convincing sense of desperation and resignation.

The Sunday Times (Jonathan Dove’s “Flight”, Glyndebourne Festival 1999)

.jpg)

Christopher Robson is exceptional as the Refugee, the clarion power of his countertenor voice commanding the evening.

The Sunday Telegraph (Jonathan Dove’s “Flight”, Glyndebourne Festival 1999)

Christopher Robson sings superbly as the Refugee, consistently strong and firm.

The Guardian (Jonathan Dove’s “Flight”, Glyndebourne Festival 1999)

.jpg)

Christopher Robson, as the Refugee, looks like a psychedelic tramp: marry this image with an ethereal countertenor tone, and you get a dramatic presence which is impossible to categorise.

Sunday Business (Jonathan Dove “Flight”, Glyndebourne Festival 1999)

Flight's mixture of farce and pathos as a group of staff and passengers pass a life-changing night in a storm-bound airport terminal comes magically to life on this recording, with Christopher Robson's Refugee and Claron McFadden's coloratura Controller outstanding in what is very much an ensemble production.

Daily Telegraph (Jonathan Dove's "Flight", Chandos Records CD)

Das Ensemble beeindruckt durch Spielfreude und souveräne Beherrschung der sängerischen Herausforderungen - ganz besonders hervorzuheben der exzellente Sopranist Christopher Robson, phänomenal in der Darstellung des Leidenden mit bezwingender Emotionalität in der Stimmgebung!

Opernnetz.de (Jonathan Dove's "Flight", Nationale Reisopera, Netherlands 2001)

Der Wechsel von Musik zu Erzählung und verhaltenem Spiel, der sichtbare Spaß der Sänger (vor allem von Countertenor Christopher Robson als Gast) an dem derben Humor der Vorlage machten aus der konzertanten Aufführung eine überausreizvolle Alternative zum Schauspiel.

Neuß-Grevenbroicher Zeitung (Henry Purcell's "The Fairy Queen", Globe Theater Neuss 2009)

Muntere Regieanweisungen, szenisch ausgespielte Dialoge, Konfetti und Luftschlangen für Elfenzüge und Feenzauber, die Mineralwasserflaschen auf den Tischchen nicht nur Labsal für trockene Kehlen, sondern auch, wo nötig, als Fontainen einsetzbar - und zwischendurch als komödiantische Krönung der schottische Countertenor und Bayerischer Kammersänger Christopher Robson, der sich als restlos betrunkener Dichter vom unsichtbaren Gelichter des Waldes zwicken lassen muss.

Westdeutsche Zeitung (Henry Purcell's "The Fairy Queen", Globe Theater Neuss 2009)

But what will remain longest in my ears is James Bowman and Christopher Robson in “Sound the trumpet” (Come ye Sons of Art) – a piece that has often been brilliantly recorded but has rarely sounded as exciting as it does here.

Gramophone magazine (Henry Purcell's “Come ye Sons of Art”, Virgin Classics CD)

Wenn jemand in dieser Aufführung hervorstach, dann der Countertenor Christopher Robson in der rolle des Joad: Nicht nur des hellen Timbres,sondern auch der klaren Diktion, der agilen Stimmführung und der Ausdruckhaftigkeit wegen.

Tages-Anzeiger ZH (Handel's "Athalia", Grossen Tonhallesaal Zürich)

The second reason (to buy this set) resides in Christopher Robson’s impersonation of the villainous Polinesso. He is an excellent stylist, and his characterisation is full of subtlety and intelligence. Listen to his management of the recitative, to his artful, suggestive timing in “Spero per voi”, or the expressive undertones in his Act II aria; and the technical difficulties in “Dover, giustizia” are brilliantly dealt with.

Gramophone Magazine (Handel's “Ariodante”, Farao Classics CD)

Christopher Robson ... als fieser, machtgeiler und intriganter Polinesso war er gleichwohl eine Idealbesetzung.

Süddeutsche Zeitung (Handel's "Ariodante", Bavarian State Opera, Munich 2006)

.%20Bayerische%20Staatsoper.jpg)

Christopher Robson's nasty Polinesso: unafraid of either the music or of making unappealing sounds, countertenor Robson is a super-villain in the best moustache-twirling tradition!

Classics Today (Handel's “Ariodante” – Farao Classics CD)

The prelude to Mad Tom's entry is a magical and transfiguring relief. An exhausted nature throbs on lower strings, rain is glimpsed falling through a door, while the ethereal countertenor of Christopher Robson's Edgar, feigning madness, is heard offstage. It is a transcendental moment, which ushers in the finest and most moving scene of the opera, the initial encounter betwen Lear and Mad Tom. It may seem invidious to highlight performers from among a cast who render the savagery and sadness with so committed an ensemble, but Robson's singing and acting are quite exceptional.

The Stage (Aribert Reimann's “Lear”, English National Opera)

Christopher Robson’s tattered and then vengeful Edgar bears the mark of utter control about it both vocally and dramatically.

The Times (Aribert Reimann's “Lear”, English National Opera)

Great theatrical moments: Christopher Robson's astonishing performance as Mad Tom in Lear, Ann Murray's descent into grief at the heart of Ariodante, the townsfolk thirsting for the blood of Peter Grimes as produced by Tim Albery. . . all courtesy of English National Opera.

The Independent (theatre column "Theatre on Theatre", May 1994)

... and Ometh, the "figure of hope and conscience", a Britten-like creation for countertenor, is beautifully sung and acted by Christopher Robson.

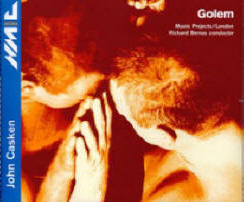

MusicWeb International (John Casken's "Golem", NMC Ancora Records CD)

Both

are also notably successful in conveying the sense of their recitative,

and so in particular is Christopher Robson, the Cyrus. His cool and

thoughtful singing gives real pleasure

The most dramatically charged performance is given by countertenor Christopher Robson as Prince Cyrus.

BBC Music magazine (Handel's “Belshazzar”, MDG Records CD)

,%20Rodelinda.jpg)

I would suggest that any young opera singer looking for inspiration in how to work on a stage should view his performance here – it’s a triumph. The perennial “little man”, despised by most, but dogged and even brave in defending what he knows to be right, Robson’s Unulfo must be one of the most affecting Handel performances I’ve seen. I have to admit to a lump in the throat as he staggers bloodied to the floor after a beating and sings of his loyalty to his King and his conviction that these storms in life will pass, in the lovely aria “Fra tempeste”.

Opera Today (Handel’s “Rodelinda”, Farao Classics DVD)

Man wohnt einer Stummfilm-Séance bei, in der der Countertenor Christopher Robson nicht nur sowohl Zuschauer als auch vielfältige Leinwandfigur ist, sondern auch ein Alter ego hat, den identisch aussehenden Cellisten Sebastian Hess, der auch szenisch (re)agiert. Robson, kahlköpfig wie Bruce Naumans "Feed me, eat me"-Rotationsvideo, wie Bruce Willis oder Kinskis Nosferatu, übernimmt teils live, teils per Video, die Rolle K's/Gregor Samsas, Grete Blochs und Felice Bauers wie des "Verwandlungs"-Personals - ein wahres Stummfilm-Panoptikum des Charakter-Chamäleonsc Robson, der phänomenal vielschichtig singt.

Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung (Hans-Jürgen von Bose's "Kafka Projekt 12/14", Bayerische Staatsoper 2002)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Eine wahrlich

kafkaeske Seelensezierung, die von dem Countertenor Christopher Robson -

wiederum als Kontrast zu dem irrationalen Geschehen - erschreckend schön

gesungen wird.

Nach Sekunden der Betroffenheit brabdeten großer Jubel und die

obligaten Buhrufe des Premierenpublikums für diese ebenso

hochintellektuelle wie tief-auslotende musikalische Psychostudie auf.

Main Echo (Hans-Jürgen von Bose's "Kafka Projekt 12/14", Bayerische Staatsoper 2002)

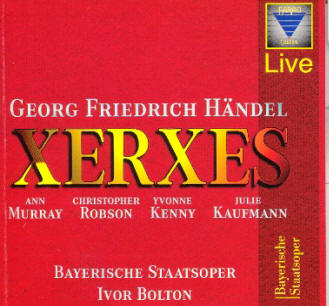

Christopher Robson’s skilfully stretched countertenor (as Arsamenes) and Jean Rigby’s luscious contralto Amastris were the only survivors of the original cast. Robson cuts a powerful figure, winning and popular with the audience.

The Guardian (Handel's “Xerxes”, English National Opera 1994)

Den glänzend eingesungenen Counter-tenor Christopher Robson (Arsamenes) jedoch störte Bickets forsche Gangart keineswegs, er brillierte als Anti-Held, tuntig, traurig, triumphierend. Von Robson wünscht man sich eigentlich nur noch den Frank N’ Furter in der "Rocky Horror Show".

Süddeutsche Zeitung (Händel's "Xerxes", Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich 2006)

Ihr zur Seite steht in der Rolle des Königsbruders Arsamenes das Countertenor-Urgestein Christopher Robson - seine Stimme ist strahlend wie eh und je und in den zahlreichen Lamenti, die die Partie bietet, kann er zu gewohnter Höchstform auflaufen: das Publikum stets so gebannt, dass man die berühmte Stecknadel fallen hören könnte.

Online Music Magazine (Handel's “Serse”, Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich)

Heureusement, pour

contrebalancer le rôle-titre, voici son frère Arsamène chanté par

Christopher Robson : voix vieillie mais ô combien intéressante,

émouvante et expressive ! Cet Arsamène ne semble pourtant plus avoir ni

l’âge ni surtout le physique requis pour être aimé de la jeune et belle

Romilda. Il est néanmoins si touchant dans sa simplicité désarmante et

dans le naturel de ses attitudes. Véritable acteur et chanteur,

Christopher Robson trouve, malgré des moyens vocaux parfois très

limites, l’expression juste, l’intonation et le geste qui bouleversent.

En somme, il est « aimable » au premier sens du mot, et le public lui

rend longuement hommage à la fin de ses airs les plus remarquables (à

l’acte I « Non so se sia la speme » et à l’acte II « Quella che tutta fé

»).

Carnet sur Sol (Handel's "Serse", Munich Opera Festival 2006)

Christopher Robson's musical intelligence and Handelian experience come

through in Arsamene's music;he sings with great passion in the group of

numbers in the middle of Act 2 (a moving F minor siciliano, a desolate

little arietta and the fiery 'Si, la voglio') and again in the very

high-lying final aria.

.. und schließlich Christopher Robson, ein abgeklärter Bühnenveteran, dem man trotzdem die Spiel- und Sangesfreude aus jeder Pore strömen sah, und auf dessen zahlreiche kleinen, aber feinen Auftritte (als Mago, Donna und Araldo) man sich immer wieder freute. .... .... Und das nicht nur im Rinaldo; denn mit Ausnahme von Alcina und Orlando war Robson in allen Händel-Inszenierungen vertreten und dadurch der herausgehobenste Stellvertreter eines weiteren, diesmal jedoch positiven Trends: der hochkarätigen Besetzung der Nebenrollen

Online Music Magazine (Handel's "Rinaldo", Munich Opera Festival 2006)

Erst der dritte Akt wird substanzieller, und dies ist vor allem der stimmlichen wie darstellerischen Praesenz von countertenor Christopher Robson (Baba) zu danken.

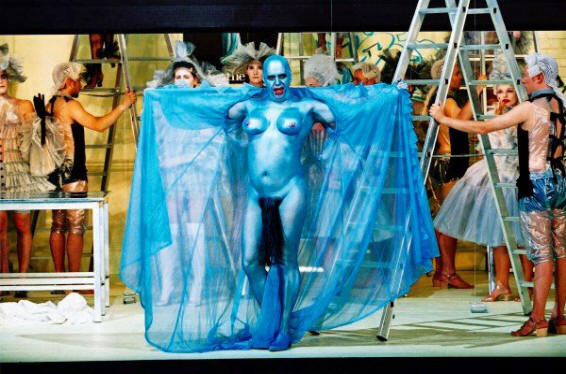

Merkur München (Igor Stravinsky's "The Rake's Progress", Bayerische Staatsoper 2003)

Graffitimaler machen sich an den Wänden zu schaffen, die Brotmaschine, mit

welcher Tom Rakewell den Hunger auf der Welt zu besiegen meint, ist ein

altmodischer Toaster, die Raritäten, welche die Türken-Baba (von

Christopher Robson als Zwitter dargestellt und brillant gesungen) in die

absurde Ehe mit Tom bringt, schweben als Luftballons unter der Decke.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Igor Stravinky's "The Rake's Progress", Munich Opera Festival 2002)

... die ganze Choreografie „Corporalitá“ ist ausgesprochen wagemutig: ...Anteil an diesem Sinnentheater hat einer der gefeiertsten ersten Sänger der Staatsoper: Kammersänger Christopher Robson.... er setzt sich mit gemessenen Bewegungen und schmerzvoller Mimik mit der Schwere des körperlichen Daseins auseinander. Doch sobald er die Stimme erhebt, sich dem „Lamento d’Arianna“ vollkommen hingibt, hat er die Materie besiegt....Stürmt die in Purpur getauchte Nike nicht doch außerhalb jeder Zeit vorwärts? Ist sie nur zu langsam für sterbliche Augen? Fragen, verstörend, aber eindrucksvoll.

AbendZeitung München ("Corporalita", Munich 2004)

... Es war ein sehr ergreifender Abend, vielleicht „der“ Abend der Kirchenmusik 2008 im Hinblick auf Emotion – aber ebenso ein Versuch, die Musik weiter zu bringen, sie auf eine neue Stufe zu heben. „Lasciate mi morire – lass mich sterben“ singt die zu Tode betrübte Ariadne — genau um diesen Stoff handelt es sich hier. Ariadne wird von einem der Countertenöre unserer Zeit gesungen: Christopher Robson. Ein Mann in der Rolle einer Frau? Das ist heute eher selten, damals aber die Normalität. Wie ging er mit seiner Rolle um? Schlicht und ergreifend hinreissend. Allein schon deshalb, weil er eben nicht den standardisierten Counter-Wohlklang feil bot, nicht nur schön und rund geschliffen. sondern auch böse, hart, gemein, verzweifelt, rau, tenoral, berstend von Gefühlen und doch mit einer berauschender körperlicher Beherrschtheit.

... Robson nimmt den Tanz bruchlos auf, gleitet nach vorne, leidet und schreit stumm, setzt dann einfach den ersten Ton in den Raum, läßt den Text fließen, fleht, ruft, schreit, haucht, lebt seine Arianna.

Rems-Zeitung, Remstal, Schwäbische Gmünd ("Corporalita", Europäischer Kirchenmusik Festival, Schwäbische Gmünd 2008)

Counter-tenor Christopher Robson's high-register vocal flutings as Fear were imbued with an eeriness that brought an added frisson to the listening experience.

Imagine what it must be like to put yourself into The Mystery Man ? He’s

sinister, like a bloated corpse, yet is he evil ? Christopher Robson

acts out the menace in the part, but his singing is by turns sensually

luscious and terrifying. The countertenor voice ranges high above normal

conversation, so defies convention. It’s wonderful for expressing

complex things and mystery. No wonder it inspires so many

modern composers.

Seen & Heard International, MusicWeb International's Worldwide Concert & Opera Reviews (Olga Neuwirth "Lost Highway" - English National Opera 2008).

The Times (Olga Neuwirth "Lost Highway" - English National Opera 2008)

Besonderen

Applaus gab es für Christopher Robsons Barbara-Streisand-Jazzausflug.

Sie alle (die zu loben hier der Platz nicht

ausreicht) spielen sich souverän durch den Szenenreigen,

dessen surreale Künstlichkeit unterstrichen wird durch

den brillanten Counter-tenor Gesang von Christopher

Robson (einfühlsam begleitet von Valery Brown am Klavier)

und die elektronischen Klanglandschaften von Mark

Pölscher.

Badische

Neueste Nachrichten

There is genuine dramatic frisson delivered by the

ice-cold counter-tenor of Christopher Robson as Edward

Kelley, the psychic or "scryer" who became

Unter

den Opernsängern beeindruckt besonders der Countertenor

Christopher Robson, der den Alchemisten Edward Kelley

spielt und mit seiner Falsettstimme und seinen

Versprechen, mit den Engeln sprechen zu können, den

Wissenschaftler Dr. John Dee immer tiefer in die Welten

der Mystik hineinlockt.

Der Spiegel

02.07.11.

.jpg)

Financial Times 03.07.11.

Vor allem aber schafft Norris auf diese Weise auch zwei Ebenen, die

es Albarn erlauben, mit natürlicher Stimme intim ins

Mikrofon zu hauchen, während die kostümierten Darsteller

unter ihm - allen voran der überragende Kontratenor

Christopher Robson als Kelley - aus vollem, geschultem

Organ singen.

Berliner Zeitung 07.07.11.

Seen and Heard International 29.06.12. (Damon Albarn/Rufus Norris "Dr Dee", English National Opera/London Olympic Festival 2012)

Although there is some confident, focused singing

from

Opera Today 26.06.12 (Damon Albarn/Rufus Norris "Dr Dee", English National Opera/London Olympic Festival 2012)

_ricjard_hubert_smith.jpg)

The best was Christopher Robson, who managed—against considerable odds—to deliver an impassioned, haunting performance as the salt-drenched medium.

Opera Magazine, Sept.2012. (Damon Albarn/Rufus Norris "Dr Dee", English National Opera/London Olympic Festival 2012)

Damon

Albarn shared vocal duties with a couple of female opera

singers and the mesmerising countertenor

Christopher Robson, who

acts as

MTV - OneFest. (Live Review DR DEE concert, April 2012)

Dee’s associate Kelley, who talks to angels, is a musical highlight: countertenor Christopher Robson weirdly cooing over a gauze of bagpipe noise.

Evening Standard 28.06.12. (Damon Albarn/Rufus Norris "Dr Dee", English National Opera/London Olympic Festival 2012)

Led by the rasping Hilton, the cast dispatch their unsettling material with conviction, not least countertenor Christopher Robson , whose gleeful madness and covetous urgency as scryer Edward Kelley find memorable musical expression.

The Arts Desk 29.06.12. (Damon Albarn/Rufus Norris "Dr Dee", English National Opera/London Olympic Festival 2012)

_______________________________________________________

INTERVIEWS & OTHER ARTICLES

A Dirty Business; Musical theatre is not to be taken lightly

.jpg)

.... At the other end

of the scale, counter-tenor Christopher Robson is doing the same thing

as Oberon in Britten's "A Midsummer Night's Dream". Whether bewigged,

baroque and ballsy in Handel's "Xerxes" or reducing audiences to tears

with the painful beauty of his Mad Tom in Reimann's "Lear", Robson has

been at the forefront of performance in a discipline not noted for its

sense of theatre. He bemoans the conventionalism that still stalks the

form. "Too many people believe opera is merely about singing. Students

are brainwashed into thinking that how they sing is more important than

how they perform." This is not a charge likely to be laid at Robson's

door. Near the beginning of his operatic career, he worked with the

trailblazing David Freeman at Opera Factory and it changed his work

completely. "I suddenly saw how opera could be. Most performers are

frightened by the stage, but I'm not. I want to explore what we're

trying to present to the public. Within the terms of a production, I can

give a different performance every night." The key to his work is that,

unlike singers who wish to safeguard the purity of their voice at all

costs, he is unafraid of taking risks. In contrast to the absurdity of

Pavarotti wandering offstage halfway through the Act Two duet in "Un

ballo in maschera", Robson never sacrifices the dramatic impetus in

order to sing beautifully.

The Independent (Arts & Entertainment column "A Dirty Business", May 1995)_

_________________________________________________________________

%202.jpg)

Tenor, Countertenor, Robson and Robson

Meet Robson & Robson, by David Benedict. Brothers Nigel and Christopher bring intensity and intimacy to Handel's 'Theodora'.

You're an opera director and you're re-casting your latest hit. There

are two key roles for tenor and counter-tenor, brothers in arms, whose

friendship has been forged in battle and who have saved one another's

lives. Your singers have to convince an audience of the passionate

struggle between religion, free will and political duty. Whom do you

cast? Peter Sellars's inspired answer is the brothers Robson.

The

case of singing siblings Nigel and Christopher isn't unique, but it's

damned rare. The soprano Kristine Ciesinski has a mezzo sister,

Katherine; Terry and Neil Jenkins have been known to play Happy

Families, but discounting the Everly Brothers and the Nolan Sisters,

that's about it.

What

is unique about the pair of them, aside from the unusual pairing of

tenor and counter-tenor, is their acting talent. These two aren't just

international soloists who sing on stage, they are genuine operatic

animals. Cast either of them and you can wave good-bye to the

old-fashioned "stand and deliver" performance style. Both are more than

capable of producing honeyed tones, but these two give you something

bolder, richer and altogether more theatrical. Some directors (and

particularly record producers) favour evenness of sound above all else.

It's a little reminiscent of the Tebaldi and Callas debate: purity

versus passion. Luckily for anyone going to Glyndebourne's inspirational

staging of Handel's oratorio "Theodora", Peter Sellars has opted for the

dramatic approach.

What

he cannot have known is just how ideally suited these two are to playing

the roles of the Roman commanding officer Septimius and his friend

Didymus, a convert to the forbidden faith of Christianity. The Robsons'

parents were officers in the Salvation Army, but they are both keen to

dispel any notions of bible-bashing and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit-

style repression. Not only was theirs an enlightened evangelical

environment, music was central to their lives. They sang constantly and

played brass instruments in the Salvation Army band. "We even sang grace

around the table in slightly improvised four-part harmony," says Nigel,

the elder of the two, and the second of four sons. Their father was

constantly writing music for the church but, again, not the imagined

four-square English hymnal stuff. Nigel remembers that, as early as

1948, within three years of its premiere, his father had the sheet music

for two arias from Britten's "Peter Grimes" that he wanted to sing.

"It

was all part and parcel really. We were encouraged in music," observes

Chris, the counter-tenor, "but there was never any pressure, just as

there was no pressure to stay in the Salvation Army. There was no

pressure on us to do anything other than what we chose to do."

Neither of them is a practising Christian any longer, but their father's

influence is there for all to see. Both have reputations as 20th-century

music specialists, traceable back to their monthly record allowance and

their father's encouraging them to listen to Tippett, Messiaen and

Stockhausen. He was also responsible for their interest in performing.

"Dad used to do these evangelical musicals," says Nigel, "cobbling

together bits of operetta and so on. It feels a bit embarrassing looking

back." ("Awful," laughs Chris.) "Things like Salvation Ship Ahoy!, a

sort of Billy Budd for the Lord." ("Jesus saves / in the waves," giggles

Chris.) "He also did this strange thing, Three Faces of Eve, which was

bits of a play plus Vaughan Williams's music for Job, over which he

narrated the story of creation while people would mime it in some way,

like dance."

Yet,

for all their mixed feelings about the "church operas", both brothers

recognise the experience as having ignited very strong feelings in them

about theatre. Professional singing, however, was not immediately on the

agenda. Nigel went to

"My

voice came down very slowly over a year," he recalls. "When I went to

Cambridge Tech, aged nearly 17, it had settled into a light tenor /

baritone, but I didn't sing. Then, at the beginning of my second year,

someone heard me mucking about in the practice room and said I should

have lessons, so I started singing tenor. One day I went straight from a

trumpet lesson to a singing lesson, which was unusual. When I read the

music, having been hearing the higher pitch on the trumpet, I read it

wrong and sang an octave too high." Impressed, his teacher told him

that, to allow the counter-tenor voice to settle, he shouldn't sing for

a while. "Of course, I just went away and practised."

Music college was a disaster. "I was slung out in the middle of my

second term. Some say my musical education really began then," he says.

He started lessons with Paul Esswood and Helga Mott - he stayed with her

for 10 years - and within 12 months was earning a living, doing

everything from deputising in church and cathedral choirs, to pop sessions at Wembley

Studios and radio jingles.

"The

goals were to make a living and to make the sound as pure and straight

as possible, because the majority of the work was ensemble singing. Now

you can sing with a bigger, fuller voice, with vibrato, with much more

vocal freedom."

As

last year's jokey The Three Counter-Tenors disc shows, there is no

longer one counter-tenor sound. Each of those three soloists has a

distinctive timbre. While Chris was developing his sound in the wake of

the 1970s counter-tenor boom heralded by the ascendancy of James Bowman

- "a wonderful big voice, like a trombone," says Chris - his brother was

studying singing at the

It

was the Australian director David Freeman who brought them together and

changed their lives. He had already cast Chris in his celebrated English

National Opera staging of Monteverdi's "L'Orfeo", when the scheduled tenor,

unable to cope with Freeman's dramatic demands, pulled out a week into

rehearsals. Chris suggested engaging Nigel, who had just left Glyndebourne, and,

after auditioning for Freeman and conductor John Eliot Gardiner, he too

joined the company.

Chris credits Freeman with opening up his latent desire to improvise and

perform, and the pair of them thrived. Nigel describes it as a shared,

daring, idealistic desire to see how far Freeman's discipline of

improvisation and characterisation could go in finding ways of speaking

to an audience. "He created parameters for a performer, making us create

a character who then played the role," says Chris. "That made it easier

than just going in and playing L'Orfeo." They relished the shared

responsibility for a piece, working with a director who liberated the

performer, allowing them to discover things for themselves, something

far more akin to theatre than the intensely formal, hierarchical world

of traditional opera rehearsals.

The

release of their dramatic powers ensured them distinctive operatic

careers. They have both excelled in mad scenes, Nigel playing a powerful

Madwoman in Opera Factory's production of Britten's

Their religious upbringing has resurfaced, unbidden, in "Theodora". For

Chris, "one of the reasons I have been so forceful about Didymus the

convert being so completely enraptured by his conversion is possibly a

subconscious reaction to believing that this is a very real

possibility." Nigel sees the religious parallel in wider terms. "One of

the greatest gifts a parent can give to a child is a feeling of

responsibility about making their own mind up. Not everyone has that.

That feeling of freedom about religion lies at the heart of Theodora."

Whatever their thought-processes, the intensity of their scenes together

in rehearsals has moved at least one observer to tears. Their next joint

project may move audiences in yet another direction. Producer Jean

Nicholson is hoping to present them in the title roles of an opera based

on Genet's "The Maids", specially commissioned from composer John Lunn

and director Olivia Fuchs.

They are still negotiating the rights, but a 25-minute workshop of a

couple of scenes has already yielded exciting results. As in Theodora,

the intimacy between the characters is lent an extra charge by their own

relationship: the epitome of sibling rivalry and love. How much more typecast can

you get?

The Independent (Interview published 19th October 1996)

___________________________________________________________________

SUSSEX LIFE MAGAZINE (July 2005)

.jpg)

Photograph - Christine Schneider © 2004

Treble Maker

PROSTHETIC breasts, thighs, the whole lot, oh yes, and an elongated

Skull," said Chris Robson. "They were the most physically demanding

aspects of playing Akhnaten. It took seven hours in make up before the

show to glue me together, and then I was on stage for three hours,

followed by one-and-a-half hours to remove all the glue and

prosthetics!"

For

Chris, the expelled former music college student who has enjoyed over 30

years as a successful Countertenor (the highest male singing voice),

playing the title role in Philip Glass's opera about the enigmatic

Egyptian pharaoh was yet another new experience.

However, he has never been conformist in his approach. When told to

attend three concerts as part of a weekly music analysis class project,

Chris chose to see Pink Floyd live at the Rainbow Theatre in

Chris

who moved to East Sussex in 1999 and quickly fell in love with "the

beauty of the county, its

contrasts in landscape, the woodlands and the Downs" developed an

interest in music at the age of eight when he took up the trumpet and

his brother performed in The Joy Strings, a Salvation Army pop group. By

13, Chris was more serious about the trumpet than anything else and also

heavily into 20th century classical music. He took up singing as a

second subject and soon found he was better at singing than playing the

trumpet.

One

day as a student at

"Then

I went as a deputy to John Eliot Gardiner’s excellent Monteverdi Choir,

and continued as a full-time member for about 15 years," he says.

"Concert work as a soloist began in 1975-76, and one season with Musica

Antiqua at

Strong family connections have remained throughout Chris's career, and

involved several stage and concert performances with his elder brother,

the tenor Nigel Robson. Chris says: "We had an opera written for us by

composer John Lunn called 'The Maids'. It was based on the famous play

by Jean Genet and it had a three-week run at the Lyric Theatre,

Hammersmith, as well as a short tour to

Chris

recently did a “one-man” opera in

Chris

met the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher when she attended, with

Mikhail Gorbachev, the première of the ENO Soviet Union Tour in

Equally, times of great personal trauma have had quite a positive

influence on his performances. He says: "It's true of most things; I'm

able to express myself on stage if not in private. Performing on stage,

particularly when you're being given plum roles, you're able to bring

yourself to them, to make it unique, and express everything you're

feeling to people, without them even realising or causing them trauma.

It's a great way of unburdening yourself as well as exploring yourself

and the role. "Lesley Garrett and I worked together in Handel’s

“Ariodante” at the ENO, and I played a really nasty, manipulative

character, which at one point virtually rapes and beats her. The

audience had to find the character revolting and loathe him. Lesley had

to confront her ghosts and learn how to discipline them, as did I, and

use them to tell the story. It was a real journey for both of us."

By

his own admission, Chris is not always seen as an easy person to work

with. He says: "Some would say I'm a bit difficult. Others would say I'm

a bit weird. Most would, I hope, say I'm a good person to work with.

There was one conductor in particular who I didn’t get on with; once I

just had to stop singing half way through an aria, and he didn't even

notice, because he was so busy singing my part while he was conducting

with his head buried in his score."

Chris

moved to East Sussex from London in the summer of 1999, when his partner

at the time became Production Coordinator at Glyndebourne. By

coincidence he was also engaged at the Glyndebourne Festival at the

time. Last December Chris moved from his rented house in Maynard's Green

to a house just outside the

Last

November Chris sang at the gala premiere of the film of Shakespeare’s

“The Merchant of

Margaret Paxton, SUSSEX LIFE Magazine (Interview published July 2005)

.jpg)